Forget 2100

Published:

What will the world look like in the year 2100?

If we can avoid nuclear winter, robot overlords, or some unforeseen apocalypse, then the question is really about climate change. The answers, of which there are many, have to do with global temperatures, sea level rise, ocean acidification, species extinction/collapse, drought, and storm intensity—just to name a few. These predictions don’t always agree, but one commonality is that the time frame is on the scale of decades to century.

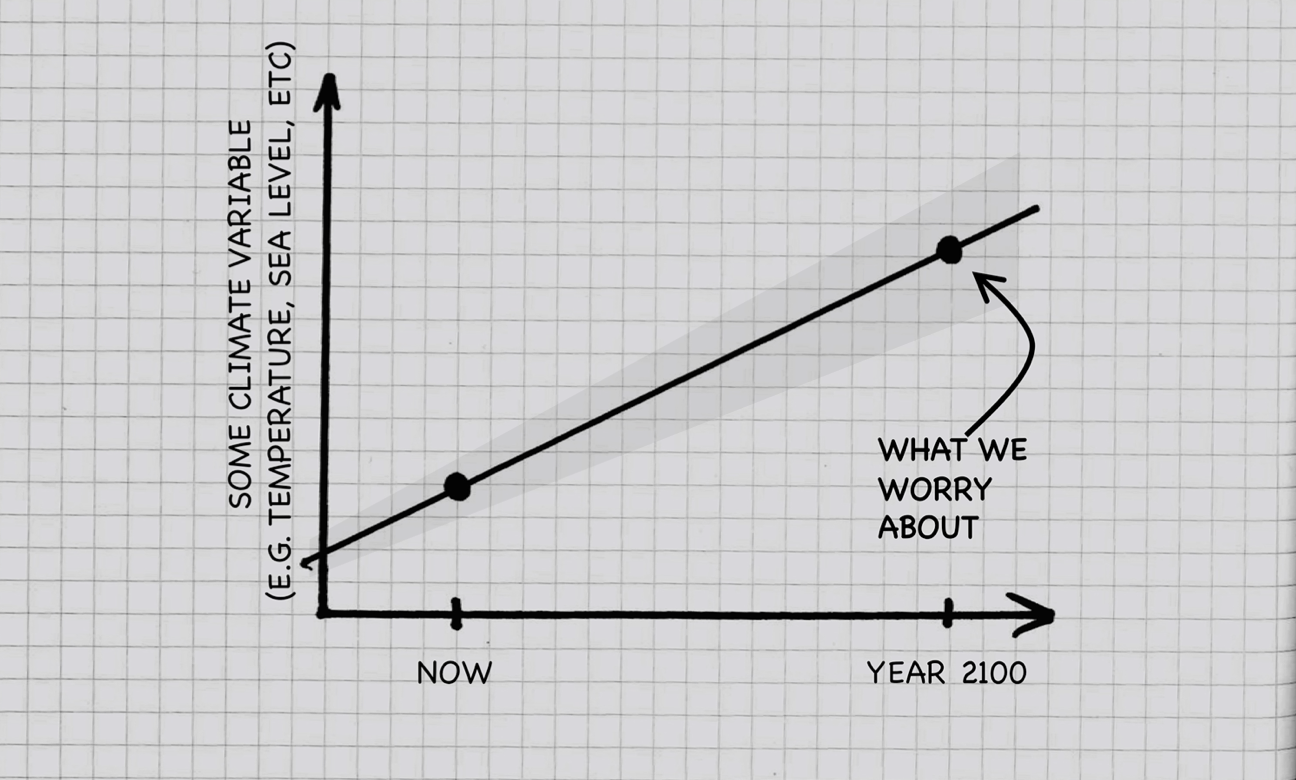

A lot of the projections in this vein look something like this:

The graphs that you see might look a little more technical that this one, but the basic idea is the same–there’s a trend line with maybe a cloud of uncertainty around it. The message is about how average conditions will change over a long period of time.

This kind of calculation is useful, and climate scientists can often make them with reasonably high certainty. But the graph itself makes a particular imprint in our minds of what climate change looks like–a gradual but steady change over a long period of time. I think that it guides our minds to focus on that distant horizon—the year 2100. It’s common to hear about acting on climate change because of the world we’re leaving for our children or grandchildren.

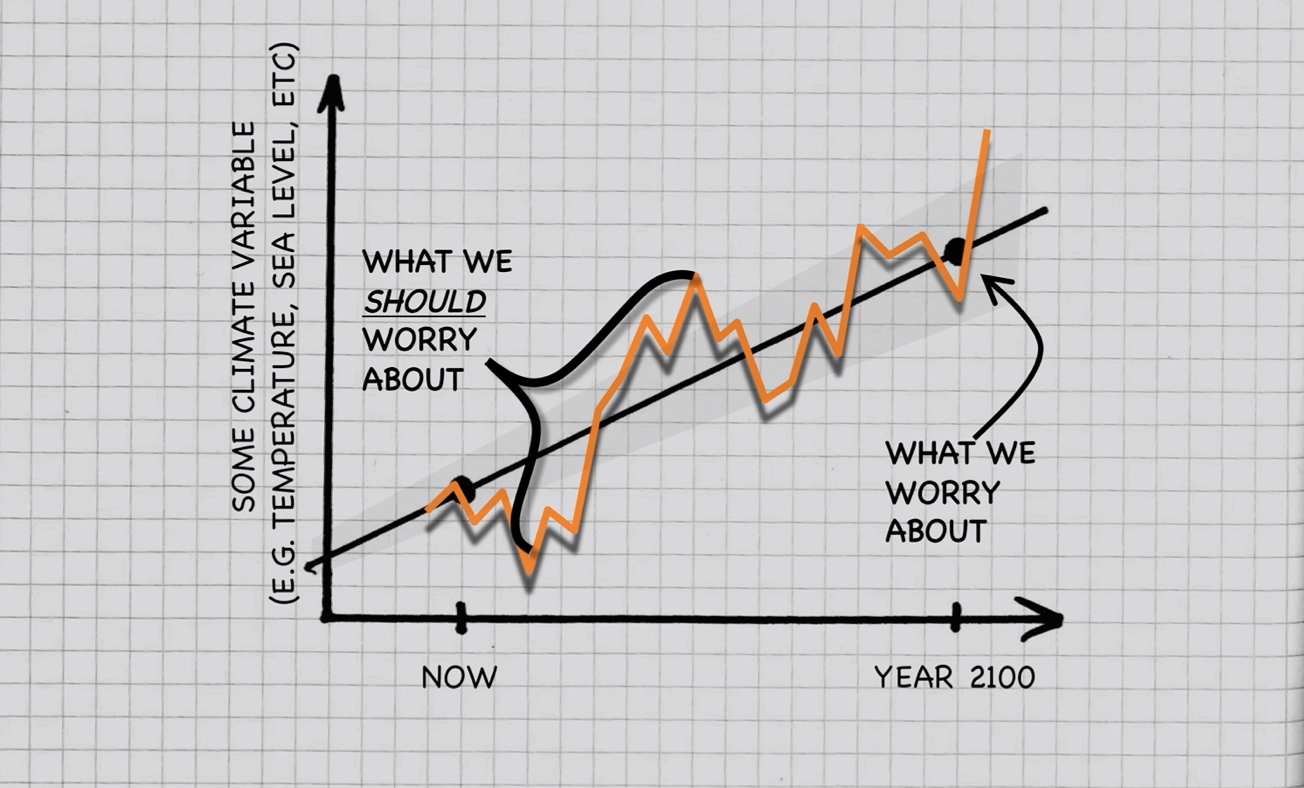

The problem with that smooth, gradual line is that it misses all of the bumps and wiggles along the way. Those ups and downs are the variance around the line, and in equally technical cartoon form, they look something like this:

Along the way to those unsettling 2100 conditions are sharp increases (and decreases) that occur over short time periods. This is the reality of climate change that we have to deal with, and it arrives much sooner than 2100.

Bouts of rapid warming will occur in different places at different times, and we’re already starting to see some of them popping up. The recent rapid warming in the Gulf of Maine is an instructive case (e.g. see links here, here, and here ). Recent warming of ocean temperatures in this location has been almost 10 times as fast as the background warming rate and faster than 99.9% of the rest of the ocean. It’s a rate of warming that has been extremely rare among marine ecosystems. This coastal sea has essentially gone through one of those big bumps/wiggles, already arriving at conditions close to the year-2100 projections.

The rapid warming has turned the ecosystem on its head. From seahorses in lobster traps to mola molas chasing jellyfish, unusual species have become the norm. For many commercial species, the temperature change was too quick for management to keep pace, leading to unforeseen collapses of once reliable stocks, such as Atlantic cod and northern shrimp. Changing currents have relocated plankton, driving endangered whales into unprotected locatoins, with deadly results. Meanwhile, along the coast, new visitors like the invasive green crab have been physically reengineering the system. (These dynamics, and others like them, make up a remarkable story that is still unfolding–a good starting point is this link.)

The Gulf of Maine may be one of the first to go through a bump/wiggle like this, but it won’t be the last. In many places around the world, we’ll find that the road to year-2100 conditions will not be a gradual slope, but a roller coaster ride. If we focus on averaged gradual patterns, we’ll overlook the places that could need climate adaptation resources more urgently. For those who are thinking about ways to prepare for and adapt to changing climate, take your eyes off the year 2100. Rapid changes that occur over short scales are arriving much sooner, and that’s what we have to respond to.

Again, assuming we can avoid the robot overlords.